Story by Ned Rozell

On a recent river trip in northern Alaska, scientists from the University of Alaska Museum of the North found a lost world, a time of “polar forests with reptiles running around in them.”

That’s a description from Patrick Druckenmiller, director of the museum and a paleontologist with the ability to look at river rocks and see the footprints of an animal that walked there from 90 million to 100 million years ago.

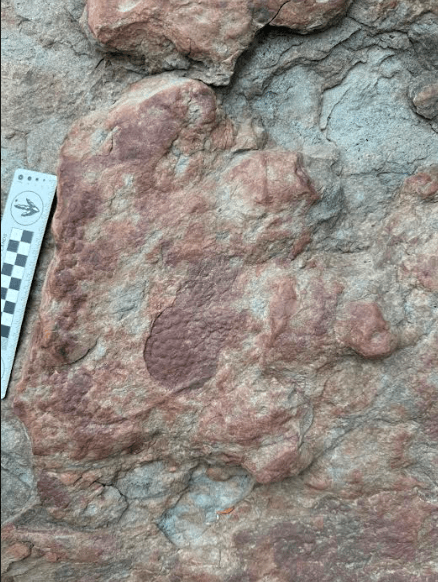

In early August 2024, Druckenmiller and his colleague Kevin May, along with Greg Erickson and Tyler Hunt of Florida State University, floated 160 miles along the upper Colville River on Alaska’s North Slope. There in the rocks on the shoreline, they found fossilized tracks of many species of dinosaur, as well as the pebbled skin impressions left behind by an armored ankylosaur and other plant-eating dinosaurs.

They captured many images of this very different time and also returned to Fairbanks with a few hundred pounds of fossils on their chartered aircraft.

With that evidence — including etchings of gingko leaves that would most certainly not grow on the North Slope today — Druckenmiller hopes to piece together a long-gone ecosystem.

“The dinosaur story in the state from the end of the Cretaceous (70 million years ago) is well known because of the Prince Creek Formation (on the lower Colville River) and Denali National Park and Preserve,” Druckenmiller said. “The older period (from 90 million to 100 million years ago) is very poorly known. And it’s a really warm interval in Earth’s history.”

How warm was today’s cold North Slope back then? From the broadleaf plant fossils and petrified tree stumps the team members found, Druckenmiller estimates the upper Colville River area had a similar climate to Washington state today.

“And (the upper Colville) was farther north at the time,” he said. “It has moved south since then (due to movement of tectonic plates), which makes it all the more remarkable.”

North of the Brooks Range — the farthest north of Alaska’s three major sweeps of mountains — the upper Colville River of today has a yearly average temperature well below freezing. But air temperatures are warming, as they did in the distant past.

“Things have changed even since I’ve been in Alaska,” Druckenmiller said. “We saw lots of slumps from thawing permafrost (defined as soil that has remained frozen through the heat of at least two summers and usually much longer). And there were these forest of willows — 25-foot high trees.

“And I heard thunder up there for the first time this year.”

With their trained eyes, Druckenmiller and his colleagues spotted in rocks tracks of three meat-eating dinosaurs, a species of armored plant-eater, another plant-eater that walked on two legs, and the tracks of bird-type animals that left the impressions behind long before modern birds had evolved.

From 90 million to 100 million years ago, those dinosaurs stepped in mud. Sometimes, sand then filled in the tracks to preserve them as molds made of stone. Other tracks appeared on rocks like footprints as you would see them if the animal had just passed.

The petrified stumps on the upper Colville River may be from sequoia-type trees that thrived in the area millions of years ago. Other than willows and scattered balsam poplars, trees don’t grow on the North Slope today.

May and Druckenmiller had visited the area before, but that was more than 25 years ago. They attributed the gap in time to the difficulty of reaching the spot hundreds of miles from the nearest community via expensive air charter, and the number of other projects that vie for a scientist’s attention during short Alaska summers.

The museum director will now carve out some time to examine what they’ve brought back from that quiet country. The details will pour through the filter of his brain. Then he will write a paper on the polar forests of Alaska and the creatures that stomped through them.